I am not an “outdoorsy” person.

I don’t own a tent, sleeping bag, camping stove, or hiking boots. I’ve never even had an REI or MEC membership.

It’s not that I’m scared of bears, sleeping on the ground, or getting cold and dirty. It’s just that I’ve never felt that escaping into the wild was worth the cost and effort.

Not until I learned about and experienced the “3-day effect.”

Feeling The Comfort Crisis

A book called The Comfort Crisis by Greg Easter is what started to change my mind.

It follows Easter’s month-long hunting trip in the middle of nowhere in Alaska. Every chapter, he narrates a different form of discomfort he experienced, then investigates the latest research on how and why it might be good for us.

Even though The Comfort Crisis covered a lot of ground I’ve tread on before—e.g., fasting, cold exposure, fitness—it ended up being one of my favorite books I read in 2021 because it taught me new ideas that changed my perspective.

One example: the nature pyramid.

Time to Climb the Nature Pyramid?

In his chapter on the beneficial discomfort of withdrawing yourself from modern technology, Easter introduced me to neuroscientist Rachel Hopman’s concept of the nature pyramid.

As it happened, I’d recently discovered on my own the rewards of hanging out at the base of the pyramid.

Two months before reading The Comfort Crisis, I did a month-long experiment of daily “empty pocket walks.” These 20-to-40-minute phone-less wanders in the woods or along the beach ended up being so counterintuitively productive that I’ve continued doing them a few times a week. And that’s precisely what level one of the nature pyramid prescribes.

The second layer is going for hikes, picnics, mountain bike rides, or whatever in parks outside of town once or twice a month for a total of at least five hours. I was probably getting about half that dosage.

But I was completely missing on level three, the pinnacle of the pyramid:

Three or more days in the wild once or twice a year.

“Wild” isn’t a glamping. It means likely presence of wildlife, no toilets, no cell reception, no beds, and few to no other people around.

When you’re in the wild long enough, you experience “the 3-day effect.”

The 3-Day Effect

The 3-day effect of escaping into nature has similar benefits to a 3-day food fast.

When you completely cut out calories, it takes a couple of days to burn your body’s glycogen stores. This transition can be uncomfortable. But when you’re through it and start burning fat for fuel, it feels fantastic.

Similarly, when you cut out multimedia, it takes a couple of days for our minds to unwind from the web of technology. Then our brain waves measurably change. We enter in a sort of flow state.

These good vibes continue to benefit us even upon returning to “the real world.” For instance, one study found hikers scored nearly 50 percent better at a creativity test after being withdrawn from multimedia and immersed in the wild for four to six days.

Easter was talking my language the way he summarized the 3-day effect:

“Three or more days in the wild is like a meditation retreat. Except talking is allowed and the experience is free of costs and gurus.”

I was keen to try.

But I had a baby to look after. And no camping gear. So I shelved the 3-day effect idea and immersed my mind into other books about other ways to make my life better without leaving town.

Until we returned to South Africa.

Invited Into the Wild

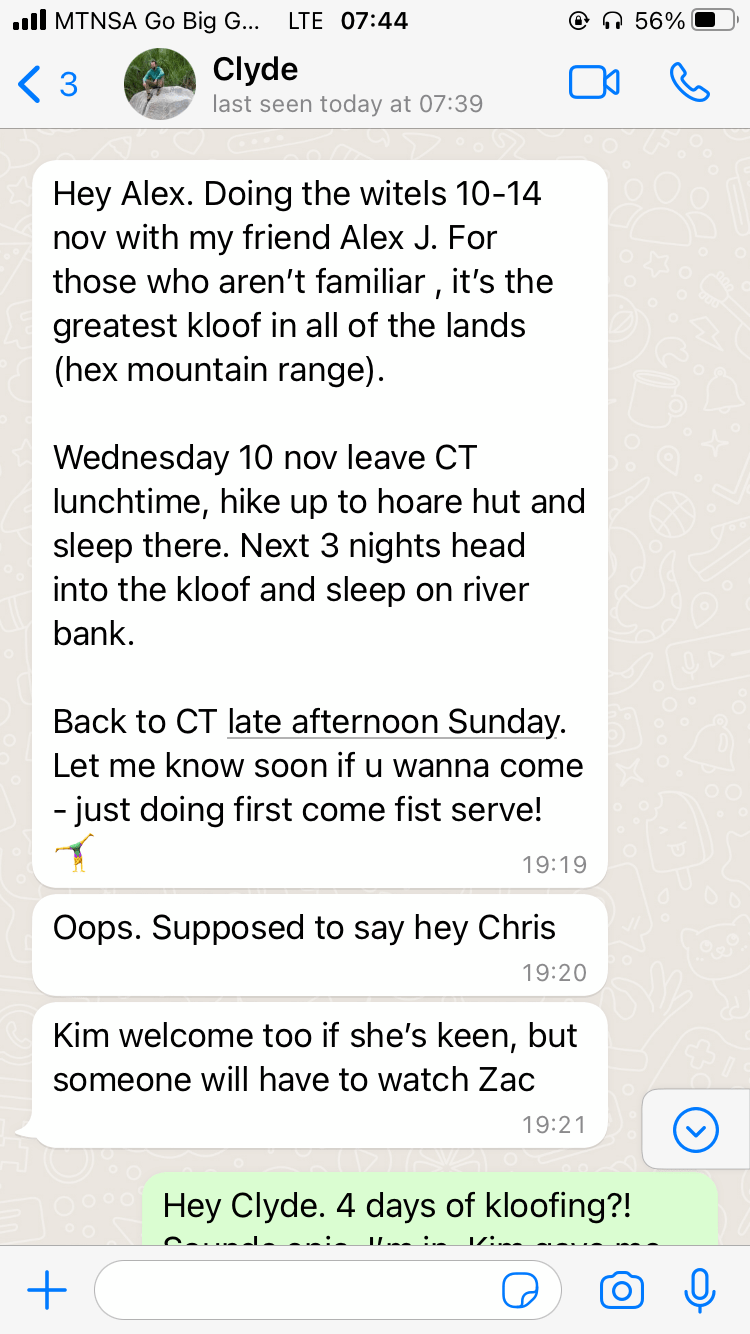

The day we arrived in our adopted second home of Cape Town, I got the following message from my friend Clyde:

It was the opportunity I was passively waiting for! A chance to climb to the peak of the nature pyramid and experience the 3-day effect for myself.

Not only that, but it was a chance to go down “the greatest kloof [South African for canyon] in all the lands.”

I was worried I was getting in over my head. But my friends were experienced. And not going on adventures because they made me uncomfortable would make me a crappy personal development blogger.

So I asked Kim for permission. She generously agreed to jump on the grenade of looking after Zac while I was gone.

It was on.

Boring Into My Mind

Three weeks later, I was in a gravel parking lot at the base of a mountain an hour outside of Cape Town, hoisting my backpack out of Clyde’s trunk.

The first afternoon and evening, we hiked to the top of the mountain, where we spent the night. Then we descended the other side into the canyon.

The next 75 hours went as follows:

- Bushwhack (or “bundu bash,” as they say in South Africa), rock hop, wade, and swim down at the remarkably slow rate of 0.5-to-1 kilometer an hour.

- Break 1 hour for lunch.

- Race to get to the campsite before it got too cold and dark.

- Unpack, rehydrate the dried dinners we’d packed, eat.

- Sleep on whatever patch of sand we could find beside the river.

- Wake up, have breakfast, and pack up.

- Repeat.

Ironically, the experience was a lot like something I thought I had looked forward to getting a break from: dealing with my newborn. It was objectively unpleasant most of the time but simultaneously, and almost inexplicably, rewarding.

But surviving in the wild offered one significant advantage over keeping a baby alive:

Way better sleeps.

And they got better and better each night. So good that, after enjoying my best sleep in years on the last night of our hike, I had a half-baked business idea:

“Sandman’s Sleep Solutions.” Beds of sand in your home, maybe with a thin membrane of some sort to keep things from getting messy.

Maybe this was the creativity part of the 3-day effect kicking in?

And maybe my better sleeps were a sign my mind had fully unwound?

I sure felt it.

No offense to Kim, but Zac was the only part of civilization I missed. The urge to check my emails or Google every stupid question that came to my mind was gone. So too were worries about my blog’s slow growth, how to make more money, and where and how to raise Zac.

Even my usually constantly-racing mind puttered to a near standstill. I’d brought a notebook for potential ideas and epiphanies. But, aside from my lifelogging notes, all I put in it was Sandman’s Sleep Solutions.

Easter’s semi-snarky point about how the 3-day effect is a low-cost, guru-free, un-silent meditation retreat was spot on.

The Most Underrated Self Help Approach (Way) Out There

My experience on the peak of the nature pyramid has completely changed my calculus on camping in the wild. I now believe the benefits far exceed the cost and effort.

The 3-day effect is real. And it comes with many other rewards, including:

- Exercise. As Easter writes about in one chapter of his book, carrying a heavy pack over large distances, “rucking,” is maybe the most natural calorie-burning, muscle-strengthening type of training there is.

- Stoic lessons. You’re reminded that even with very little, you’ll still be fine. More than fine.

- Light exposure. When camping, you can’t avoid abiding by neuroscientist Andrew Huberman‘s number one well-being recommendation: get outdoor light exposure first thing in the morning and again during sunset.

- Sleep. Not only did I sleep well, but I also slept long—up to 10 hours straight! Matthew Walker, author of Why We Sleep, one of the sledgehammer books that changed my thinking, would approve.

- Social connection. Lots of time to talk with no distraction. Plus, when it’s your group against nature, it fosters a feeling of community—even tribalism. I recommend Tribe, by Sebastian Junger, for more on this.

- Awe. The power, scale, and beauty of nature have a way of putting you in your place.

- Cold exposure. Or heat exposure, depending on where you go. In our case, getting in and out of the river had us shivering.

- Appreciation for the environment. After drinking from the stream for days, it was sad to see it merge with a river that I wouldn’t even want to swim in.

- Diet. I’m not sure if a diet of dehydrated foods and nuts is ideal, but for many it’s probably better for them than the crap they usually stuff down their throats.)

None of these benefits came easy. A walk in the wild isn’t a walk in the park, so to speak. But that’s the point.

Those discomforts are a distant memory, anyway. What remain clear as day are the rewards. So I’m looking forward to more escapes into the wild.

Who knows?

I may even get around to buying my own gear. And maybe one day I’ll even consider myself “outdoorsy.”

Read the Book

"Feedback givers are architects of ideas and catalysts for change."

Can You Help Me?

I desperately need your feedback on The Zag because I'm struggling to improve it. Please leave your quick, 100% anonymous thoughts here.

About the author

👋 Hi, I’m Chris. I help people fight complacency and self-deception using systematic approaches to live extraordinary lives. Everything you read on TheZag.com is my fault. Subscribe to my newsletter for fresh, unboring ideas every 10-ish days.

Leave a Comment